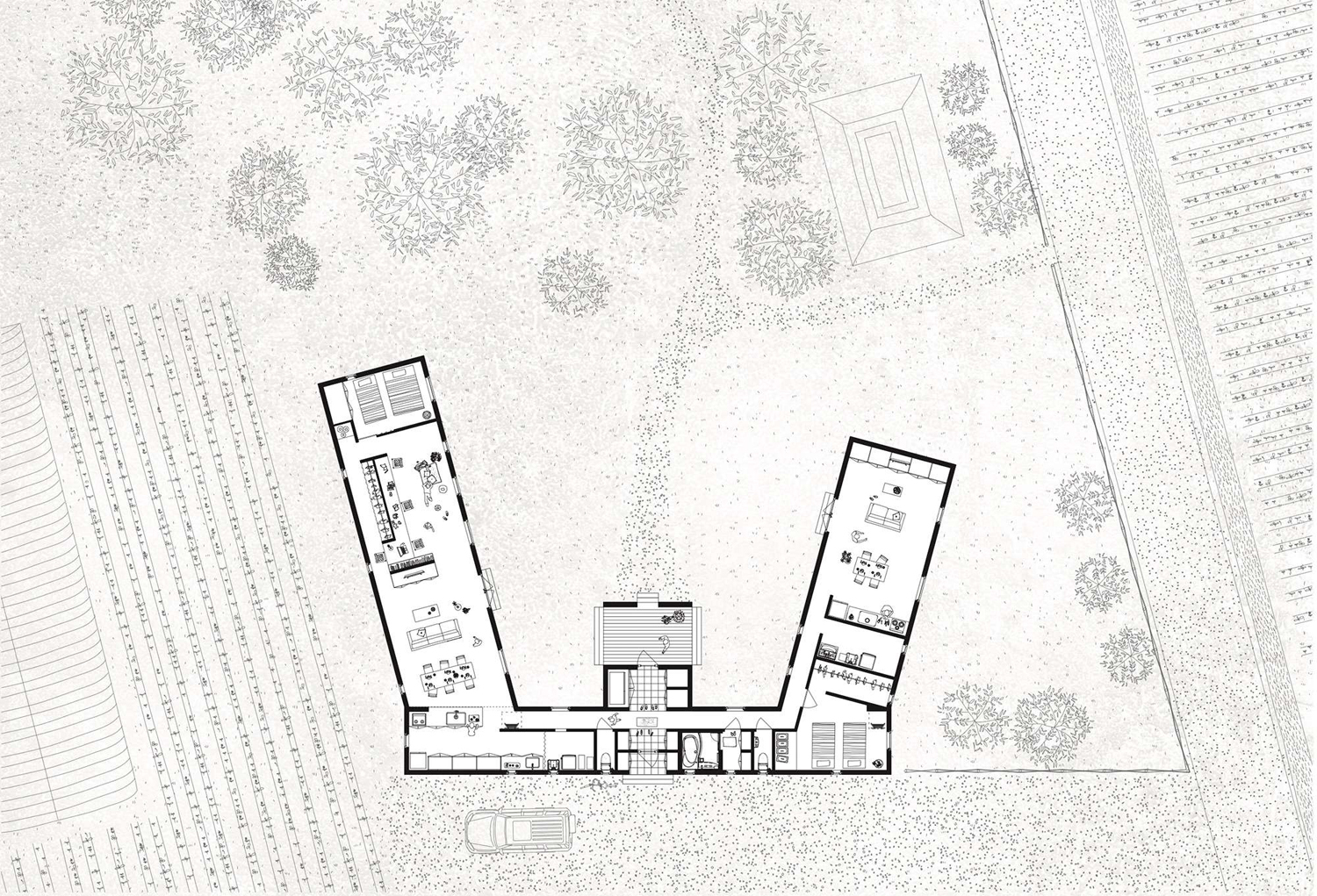

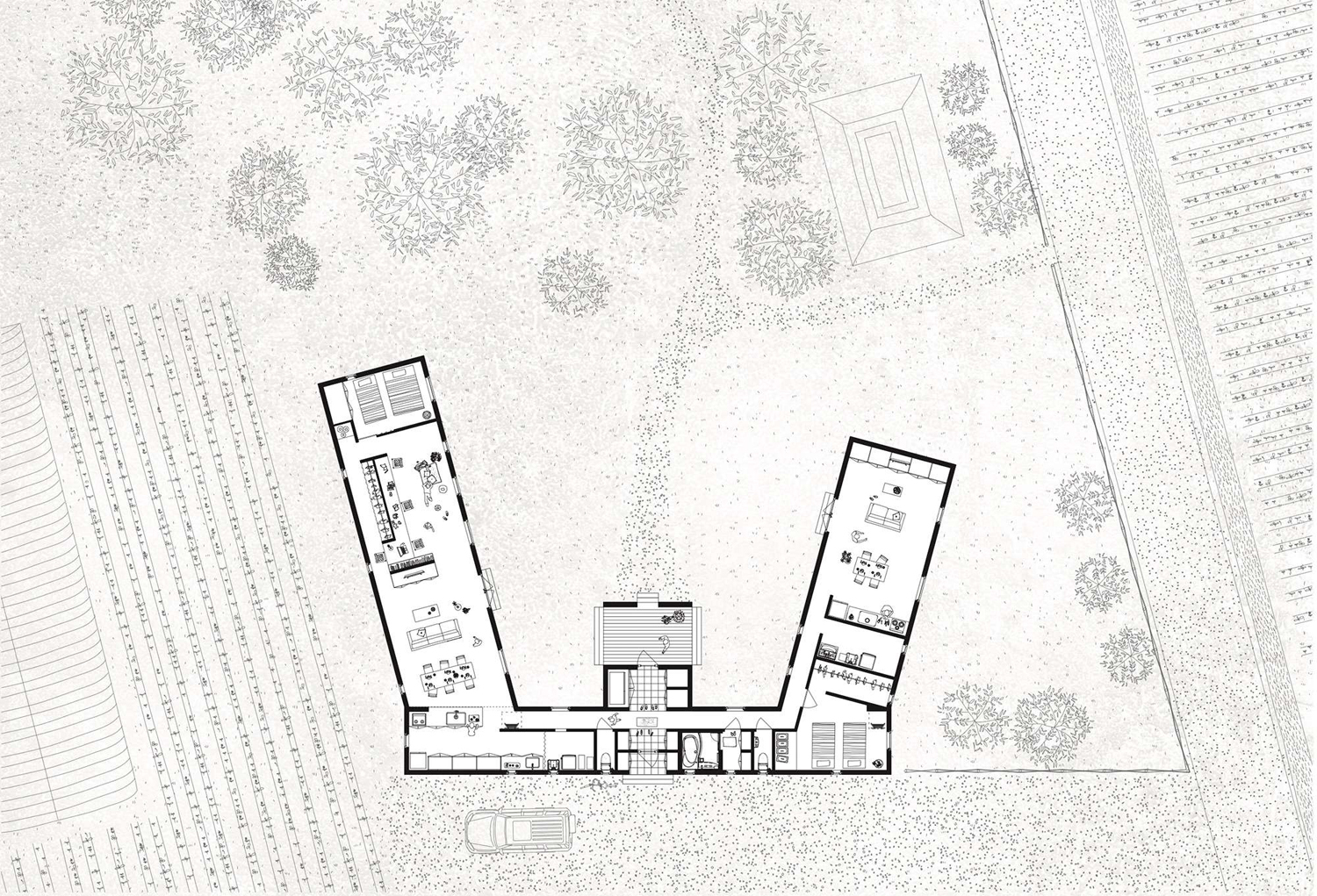

Plan of ‘Agricultural Barn’ (2008), one of Igarashi’s representative works (Courtesy of Jun Igarashi Architects)

Plan of ‘Agricultural Barn’ (2008), one of Igarashi’s representative works (Courtesy of Jun Igarashi Architects)

Igarashi: In the past, I was asked to judge at an event in which students who studied architecture in Sapporo jointly presented their graduation designs. That joint presentation was a great trial and I hoped it would continue, so in 2009 I established an organization. Activities are mainly composed of the annual graduation design exhibition, and various guests are invited to give a presentation at a lecture series, which has continued.

Sakai: Are you conscious of wanting to develop human resources in Hokkaido’s construction industry?

Igarashi: I want to create opportunities. If people with good sense get opportunities they will develop. In Tokyo, there are many lectures by architects, and up-and-coming architects teach at school part. This is quite rare in Hokkaido so I want people to be inspired by the lecture series.

When several interesting architects come to the fore in the same area, they attract attention. Whatever the field, Tokyo is the center of the media, and the central genealogy affects judgement. That’s disappointing.

Sakai: I think your architecture has two directions – one towards the client and one towards something new for society.

Igarashi: Popular buildings that exist around us are really not good constructions that share good spaces but are “things that are understood” that do not exceed society’s capacity, and those demands are increasing. I hate becoming bogged down on that side, but I’m designing amid a conflict in which I have to find a balance. I don’t like establishing the concept first. If you decide on something, all you can do is progress in a straight line. For example, it’s more fun to finally reach your destination after getting lost while walking around Asia’s narrow alleys. In want to pursue that thinking process.

Sakai: What is your take on the identity of something new that’s created in Hokkaido?

Igarashi: We often talk about Hokkaido’s identity but I feel uncomfortable with that word. During the Meiji period (1868–1912), western-style buildings were introduced into Japan; various elements, such as the climate, natural features and political background made it easy to accept such buildings. That was because they matched Hokkaido; they were not original. From a certain period, one of the Hokkaido architects I respect began designing a lot of houses with wall sidings and triangular roofs. The buildings had character but the number of builders who imitated the style increased, as if that had become an identity typical of Hokkaido. But identity is different.

Sakai: I’d like to think that there’s something that becomes apparent fundamentally, which differs from superficial identity.

Igarashi: It’s not just architectural issues; unless energy and industry and capital and a variety of things are all intricately intertwined, the real meaning of identity and natural features is never achieved. Everyone understands that, but it’s difficult.

Agricultural Barn (Courtesy of Jun Igarashi Architects)

Four Rectangles(2017)(Courtesy of Jun Igarashi Architects)

Sakai: For example, when you design the windows of a house, do you think about the scenery you can see from that window?

Igarashi: If there is unchangeable scenery, I think about it but maybe another building will be built next door. So rather than thinking about visible scenery, I think more about things like light, wind, air and heat. I think that makes it more comfortable for the people living there.

Sakai: When reading the land, what do you rely on most?

Igarashi: I always wanted to base things on the climatic conditions of the land, but in recent years the global climate is changing and so it’s hard to know what to believe. Even so, when I go and look at architecture, there is some decidedly good stuff. Even now, I don’t know what is required to create good architecture but if I did, it would become boring.

With regard to types of space, things like warehouses or shrines are the closest to the qualities of space I aim for – absolute space with tolerance, space which has no specific use and in which it is okay to do anything. Even if it becomes miscellaneous, space with a tolerance for acceptance and space that preserves the strength of piquant architecture is ideal.

Sakai: You’ve been based in Sapporo for five years now and are becoming quite dependable in terms of art and urban planning, too.

Igarashi: Sapporo is a place where even more interesting things can be done. I think there’s potential for others to be more envious of us, and for sensitive people to move here from other places. But circumstances that prevent that have continued for dozens of years, so I want to do something about this deadlock.