Understand the Original, and Restore It

vol.20Ishibashi Shoichi of Ishibashi Clock Shop / City of Sapporo

Photographs by Ida Yukitaka

Translation by Xene Inc.

Ishibashi was born in Shiranuka-cho, in eastern Hokkaido. As a child, he helped with farm work and taking care of the horses, but he says he never planned to take over the family farm.

He discovered bearing assembly through household repairs. That sparked off such curiosity about making and assembling things that he even took apart his alarm clock, and as an elementary school student he was always fussing around with machinery. During the war he enrolled in mechanical engineering at an industrial school, but the harsh wartime conditions meant school life was anything but easy.

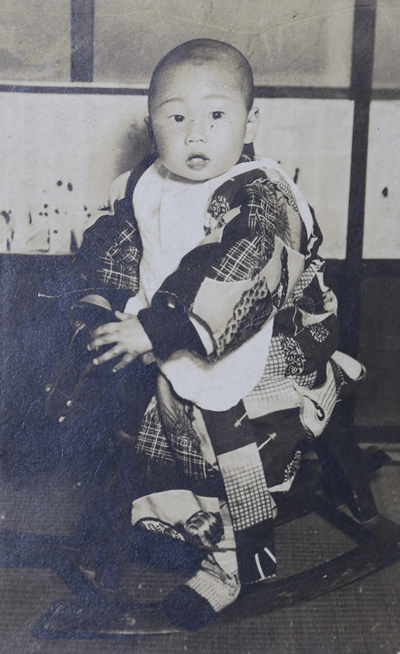

Ishibashi at around three years of age.

Repairs Included an Occupation Forces "Master & Slave Clocks"

After he graduated in May of 1946, an older graduate from his school got him a job in Sapporo. He took a night train from Kushiro to the city, and arrived in the morning. Ishibashi smiled as he remarked, "I thought I'd go visit my new company, and it turned out to be a clock shop!" The name he’d been given included the words "precision instruments," which doesn't normally imply a simple clock and watch store.

When he worked there, requests to repair high-end wristwatches came one after the other. And it wasn't just watches. He worked on German-made hall clocks, master & slave clocks used in American occupation forces hospitals, climate clocks used to measure temperature and snowfall, and more. "Working with occupation force hospitals meant I had to use English, broken as it was. The Grand Hotel was used by occupation forces as a cafeteria, and in summer the city was filled with the smell of bread and butter. Just walking down the street made me hungry!" he recalls.

He lived in an apartment with two older apprentices. He didn’t drink, so on days off his greatest pleasure was going to the cinema.

His employer took notice of Ishibashi’s sincere hard work. "When no one was around, he would come and teach me all kinds of techniques on the sly. That was my first real brush with craftsmanship, and I'm grateful" he says, with a hint of nostalgia.

"The human heart beats 60 times a minute, and a clock's second hand goes around once in 60 seconds. Humans and clocks are alike," Ishibashi says.

Tools needed for making small parts.

Boundless Curiosity

Later, Ishibashi changed jobs and took clock repair orders in one corner of a welfare society sales shop in the basement of the Hokkaido Government Building. "There wasn't a repair shop on location, so all I did was talk to customers. Customers I met there followed me when I opened my own shop."

He opened that shop in 1955. The chairman of the town marketplace approached him, and he opened Ishibashi Clock Shop in a six square meter section of the market. "A senior watchmaker served as guarantor, and I was able to buy stock on monthly installment, so I somehow got it off the ground." He didn’t sell many expensive watches to market customers, but he got a lot of repair orders.

Ishibashi's truly great point is his boundless curiosity. "A doctor starts treating patients only after he's learned the body's structure. I felt I should really learn a watch's structure better myself. When several people are working on a watch, it's easy to lose track of how it was set up to begin with." As a result, he decided to cram for the Horological Institute of America's Master Watchmaker Certification exam, and in 1960 passed the 6-day examination in Osaka.

However, before long quartz watches became mainstream, and mechanical watch demand fell off drastically. In 2010, the marketplace closed, and he considered closing his shop as well, but decided to reopen nearby. "Times may change, but clocks are still passed down from parents to children, filled with memories. That's why your goal should be to understand their original state, and restore them to that," is his message to those following in his footsteps.

73 years looking through a loupe.

Ishibashi's Master Watchmaker Certification

Ishibashi Clock Shop

Hours 9:30 to 18:30

Closed: Mondays & Thursdays

1-14 Odori Nishi 23-chome Chuo-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

Tel.: 011-611-6522