Wanting to draw architectural beauty not captured by a camera

vol.17Shimaguchi Teruo / City of Sapporo

Photographs by Ida Yukitaka

Translation by Xene Inc.

Origins in a saddlery

Shimaguchi Teruo began drawing buildings after feeling nostalgic about his place of birth, a building built in the Taisho era (1912-‘26). In 1891, his great grandfather established Shimaguchi Shoten, a saddlery producer and wholesaler by the Sosei River in central Sapporo.

Shimaguchi’s father, Shotaro Ⅱ was the first president of Orient Leather, which was established in Sapporo in 1964 and was the predecessor of the famous Hokkaido saddlery/leather goods maker, Somès (Sunagawa).

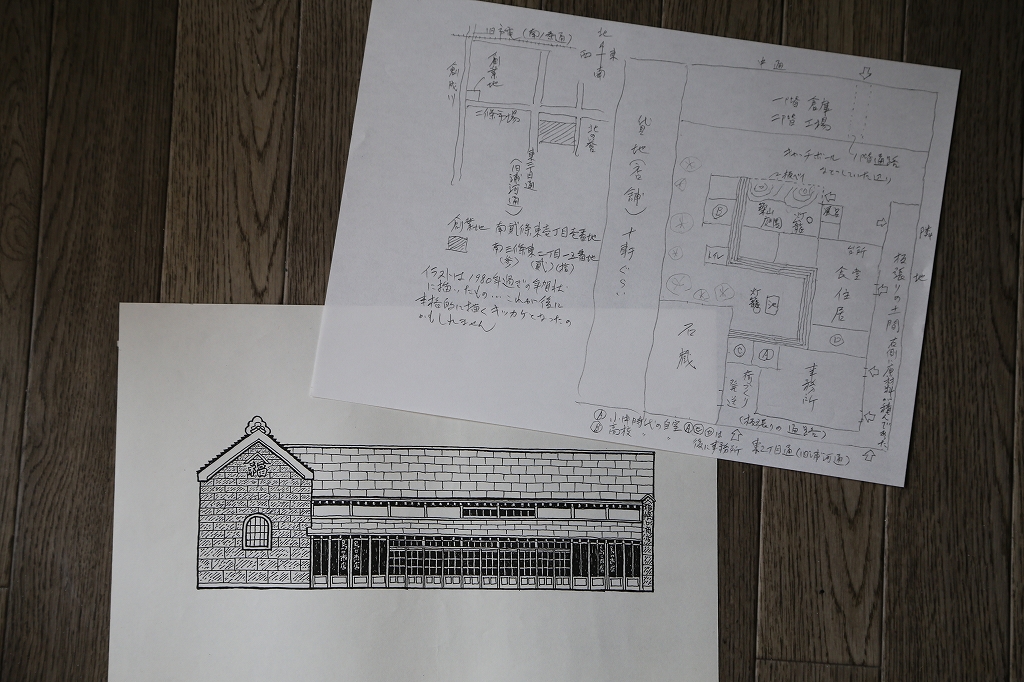

Shimaguchi began drawing buildings after drawing his birthplace 35 years ago

A saddle stand used at Shimaguchi Shoten (courtesy of Shimaguchi Teruo)

Like building up the bricks and stones

Shimaguchi began drawing architectural paintings in 1987, when he was 47 years old. After graduating from a university in Tokyo, he found work but, in his 30s, he returned to Sapporo with the intention of succeeding the family business. However, as the saddlery industry was already waning, he began to run his own independent company. At the time, a trend had begun in Hakodate in which old houses and storehouses built in the Meiji and Taisho eras were being renovated and utilized as cafés and the like. On business trips there, Shimaguchi saw these buildings and was captivated by Hakodate’s exotic charm.

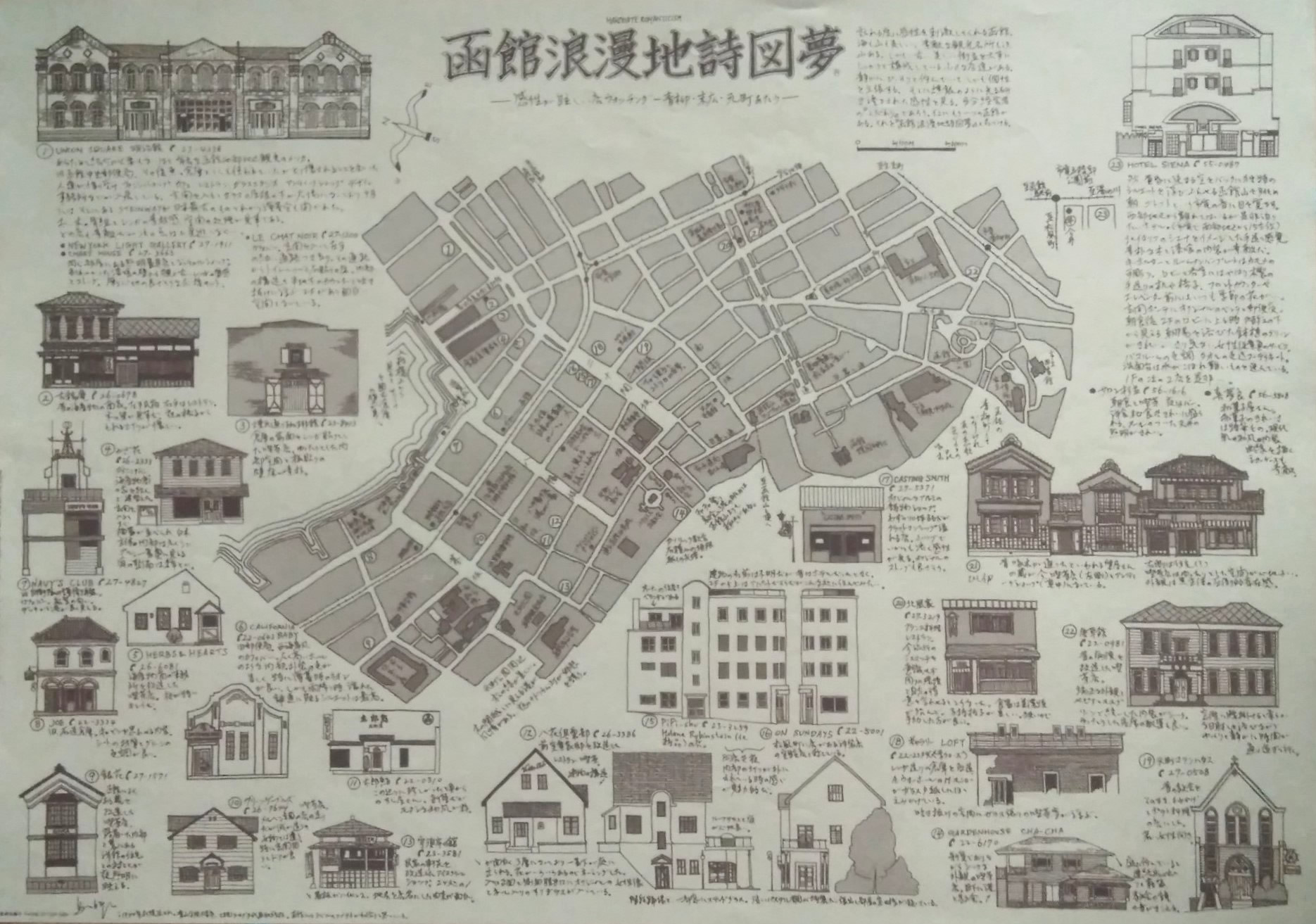

Illustrations casually drawn from photos taken in Hakodate caught the attention of a designer, resulting in Shimaguchi producing an illustration of shops, with unique impressions of the buildings along with a hand-drawn map. The illustration received rave reviews, prompting him to create Otaru and Sapporo versions, too. “I measure the size of the bricks and stones, and count the number of rows to calculate the size of the building and position of the windows and the like.”

“I’ve not received any visual arts education, and I’m not a conventional painter. From a young age, I watched craftsmen meticulously stich saddlery, so I feel my style of painting maybe reflects that,” says Shimaguchi, who became a painter at the age of 51.

His first creation was an illustration of shops in Hakodate (courtesy of Shimaguchi Teruo)

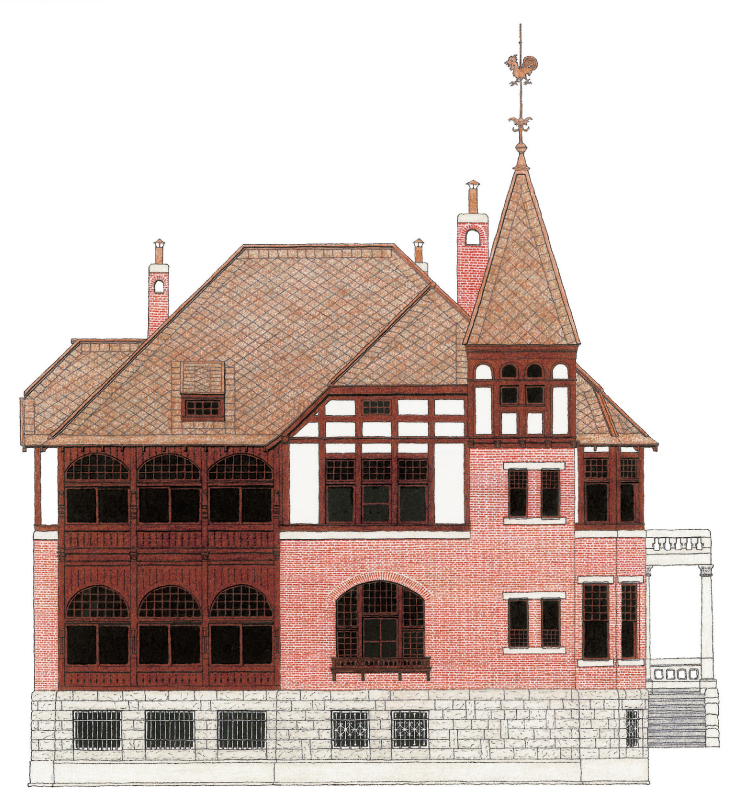

Former Hokkaido Government Office Building, 1888

Former Hokusei Girls’ School Missionary Hall (currently Hokusei Gakuen Centenery Memorial Hall), 1926

Former Nippon Yusen Otaru Branch, 1906

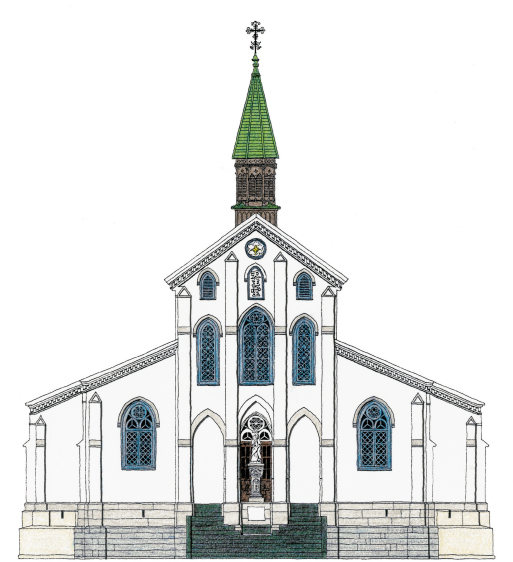

Hakodate Orthodox Church, 1916

Going with no prior knowledge

In 1992, Shimaguchi was awakened to Western-style architecture not only in Hokkaido, but also nationwide. He went on a 5,000-km car trip to take photos. “I just went with no prior knowledge, and that resulted in me being more surprised and excited than I would have been if I had done some research beforehand.”

Shimaguchi took 2,000 photos of 60 buildings in Yokohama, Kobe and Nagasaki. Among them were churches, banks and trading company buildings that collapsed in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and these famous buildings now remain in the form of Shimaguchi’s pictures. Nine of the 40 Nagasaki churches, the paintings of which took Shimaguchi three years to complete, were registered as World Cultural Heritage sites as “hidden Christian-related heritages in Nagasaki and the Amakusa region.”

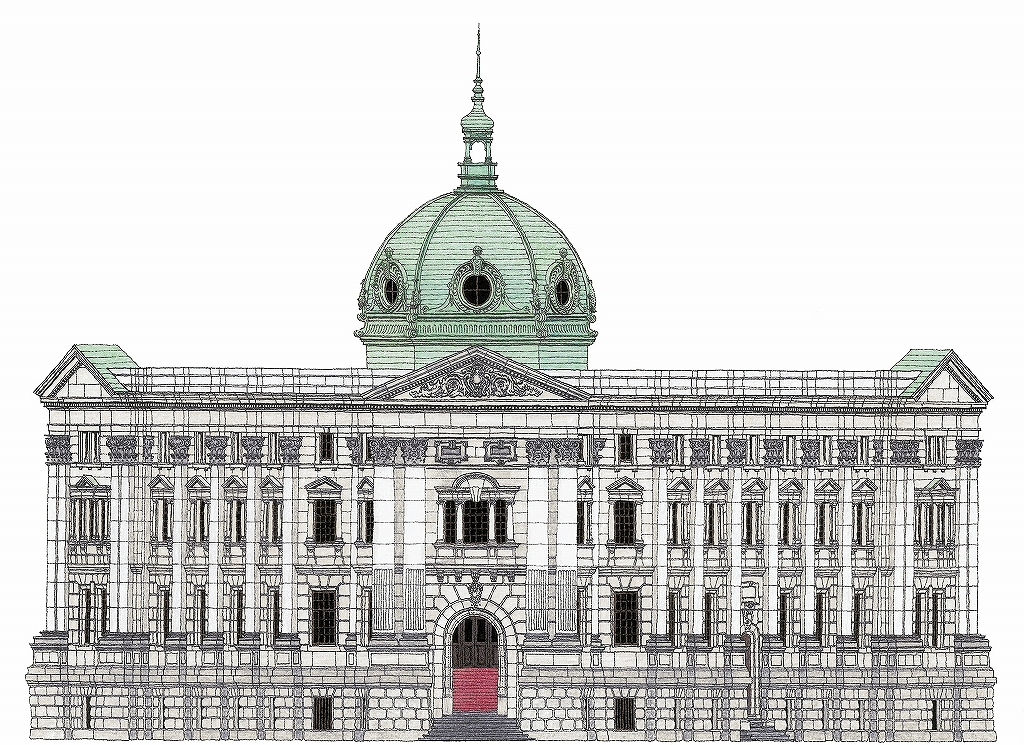

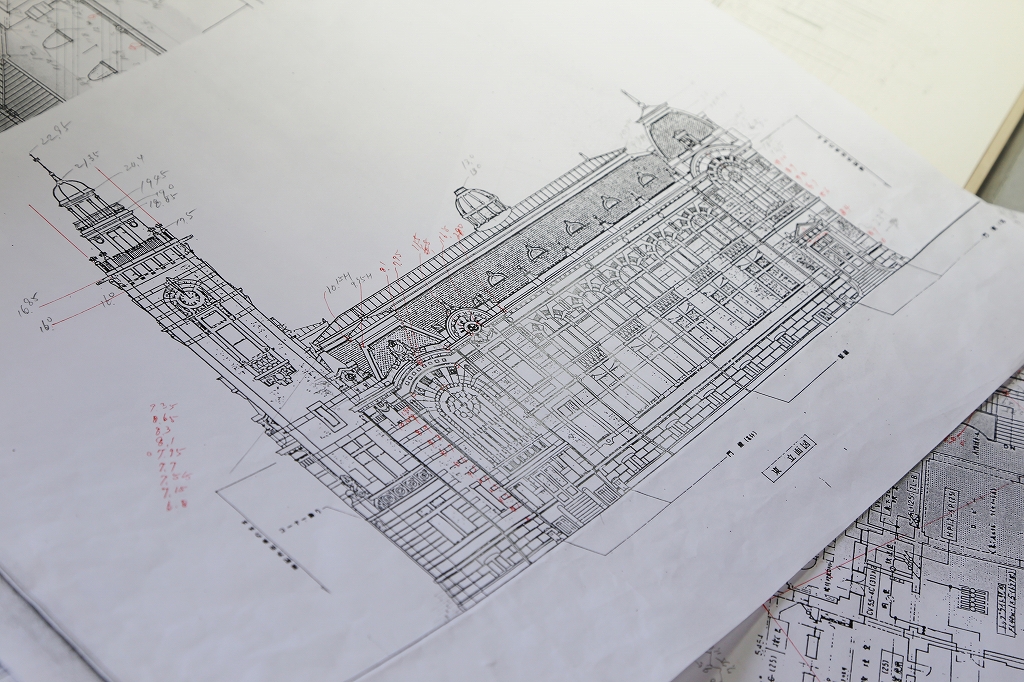

Former Yokohama Shokin Ginko (Yokohama Specie Bank) (currently Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural Hisory), 1904

Former Thomas Residency, Kobe, 1909

The oldest existing church building in Japan, and a national treasure, Oura Church (Nagasaki), 1846

A similar sense of accomplishment to that of having built them

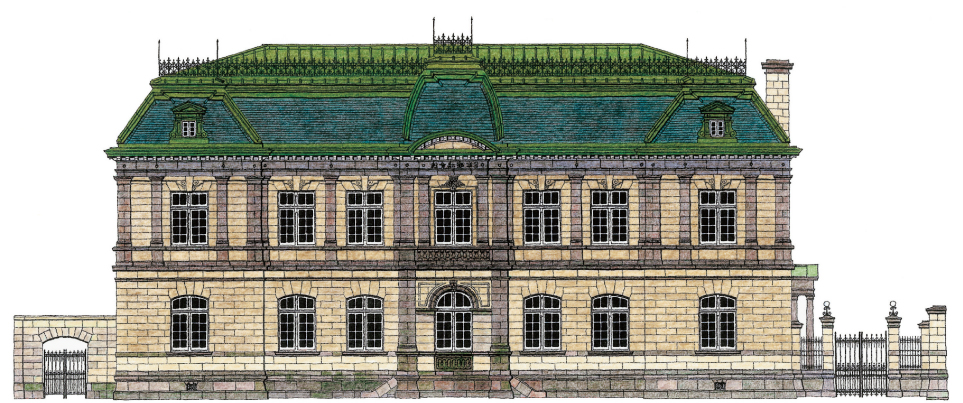

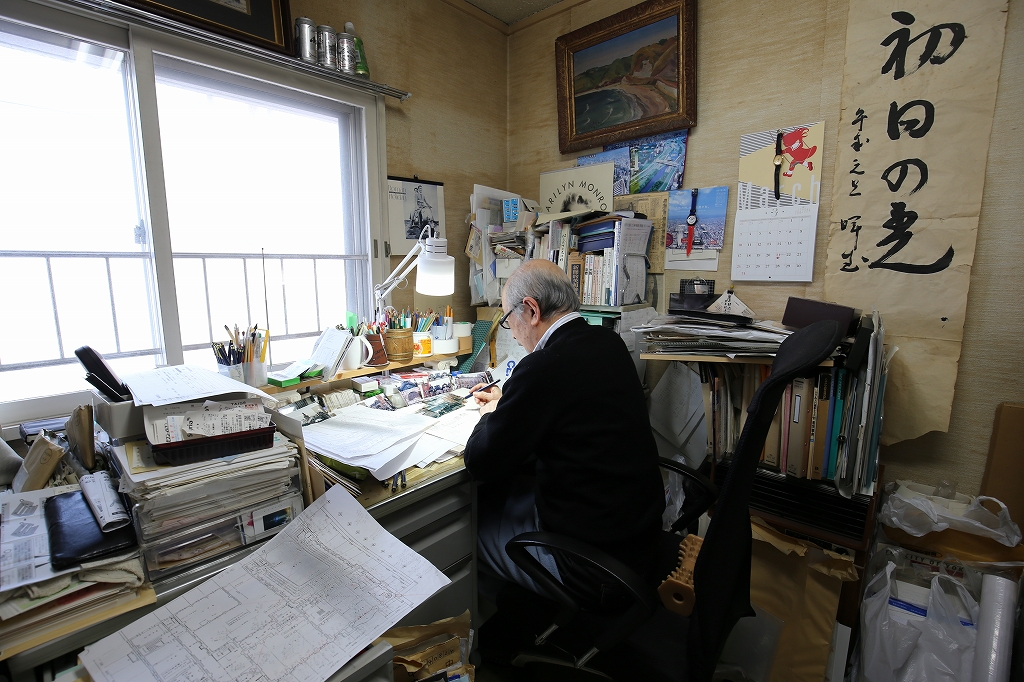

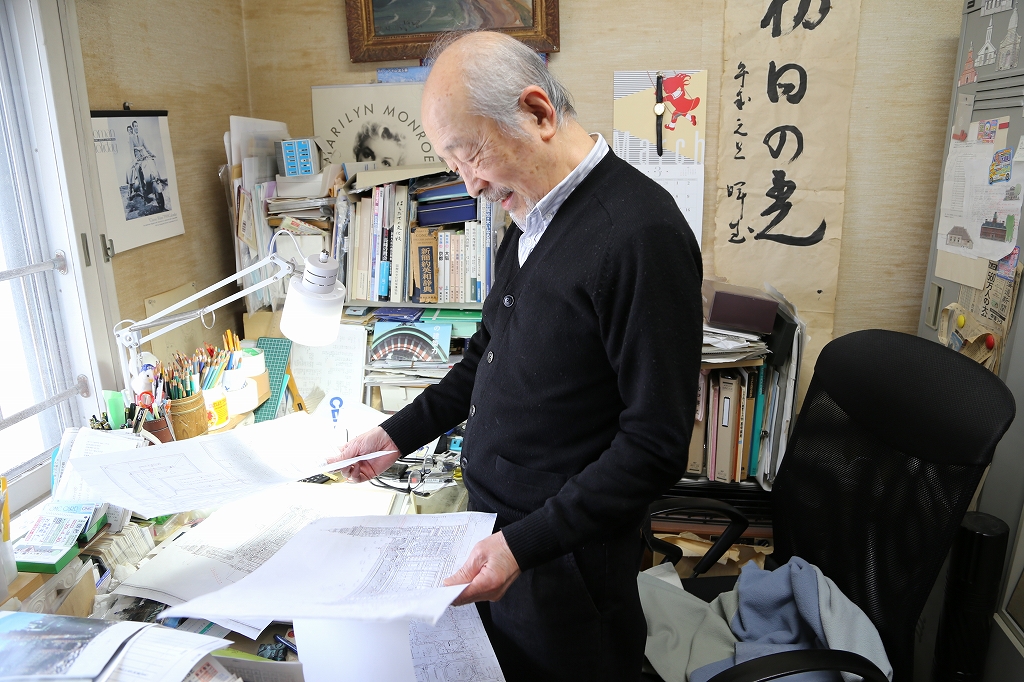

Shimaguchi’s work depicts, on one sheet, blind spots, roof shapes and other things that cannot be understood from the viewpoint of a camera or a person. The studio overflows with plans and photos of buildings, as well as essential tools, like an electronic calculator. “If I can’t get hold of plans or elevations, I draw from the photograph. I take measurements with a ruler and use the calculator to work out the ratios and determine the size of the entire building, the position of the doors and windows, and the angle of the slope of the roof. I place importance on the buildings’ proportions pursued by the architect. I want to convey the architectural beauty like the rooftop decorations and the ornamental windows or columns that cannot be seen from below.”

He has recently redrawn elevated architectural pictures by including both the façade and the sides in the same picture, which cannot be expressed in perspective style. This method was used on the Yokohama Port Opening Memorial Hall. The numbers worked out for the arrangements are written in detail on the ordered plans and rough sketches. “It’s so troublesome, I always think that I never want to draw again. But, when it’s completed, I get a similar sense of accomplishment to that of having built them, and the alcohol tastes good, too!” he laughs.

The work desk onto which natural light streams

Yokohama Port Opening Memorial Hall plans. The position of windows and ornamental parts are confirmed and measurements are written down.

Shimaguchi Teruo

E-mail:sapporomant.simagti●ymobile.ne.jp *Replace ● with @.

Website