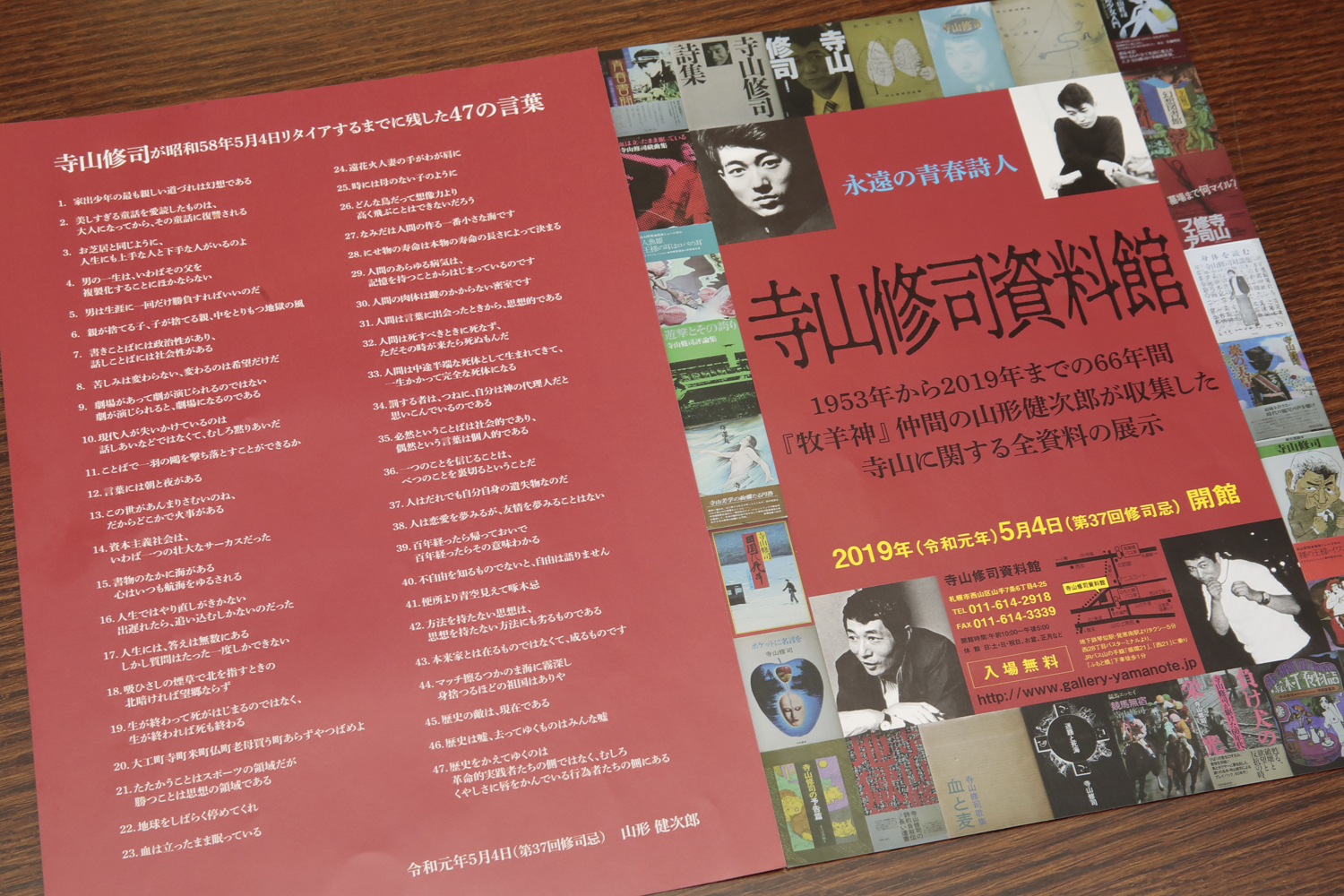

The Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo, which opened in 2019

The Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo, which opened in 2019

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the death of Terayama Shuji.

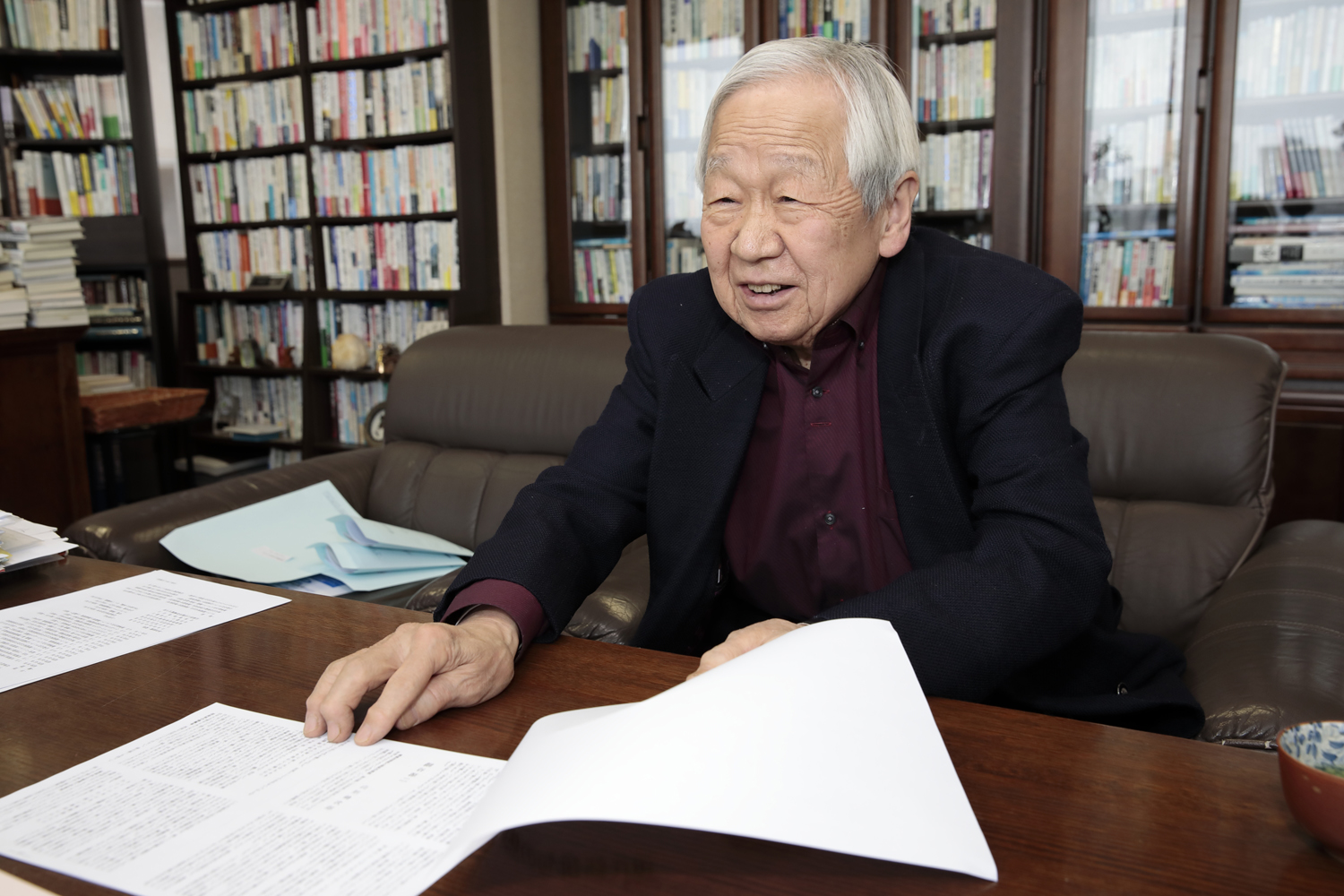

There is a person in Sapporo who knew Terayama in his younger days. Yamagata Kenjiro, 86, was one school-year younger than Terayama, and they became friends during their high-school days through their mutual love of haiku. We visited the Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo, which Yamagata opened four years ago, to find out more about the connection between the two men.

The museum displays items collected by Yamagata

The office of a company run by Yamagata is located in a three-story office building in the western part of Sapporo, the first floor of which houses the museum.

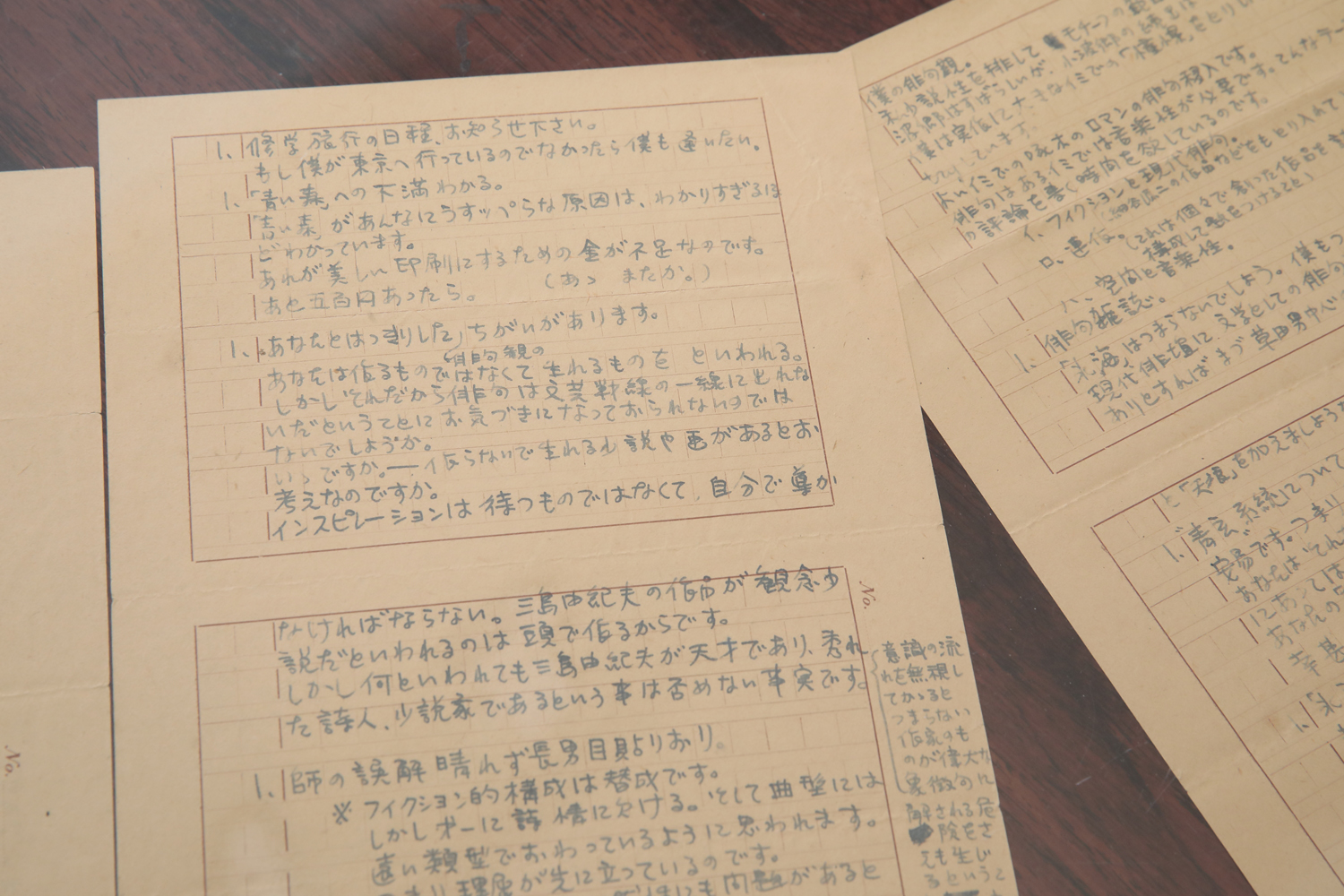

Among the many items on display are Terayama’s writings and critiques related to him; posters of performances by the theater company ‘Tenjo Sajiki’ – which Terayama presided over, as well as movie videos, CDs and more. However, what is most eye-catching is the number of letters to Yamagata, handwritten by the young Terayama.

Yamagata was born in June 1936, while Terayama was born in December of the previous year, making them of the same generation. How did Yamagata, who was born and raised in the city of Takikawa in Hokkaido, and Terayama, who was born in Aomori Prefecture, become acquainted?

“When I was in second grade at high school in Takikawa, Terayama sent a letter address to my school,” explains Yamagata. “At the time, a magazine for students preparing for examinations had a column for haiku submissions, and both Terayama and I were regularly selected to have our work published, so we knew each other's names. The name of the high school was also in the magazine, so I guessed he just sent the letter to the school.”

Yamagata’s haiku were often selected over Terayama’s. “Maybe he had his eye on me as more of my haiku were selected,” laughs Yamagata amusedly. The letter contained a request for Yamagata to join him in the creation of a haiku research magazine. Letters like this were probably sent not only to Yamagata, but to high-school students all around Japan, who caught Terayama’s eye. In 1954, just before Terayama entered university, the inaugural issue of the teenage haiku journal ‘Bokuyoshin’ was published. The museum exhibits all 12 issues of the magazine in mimeograph editions.

The letter from Terayama

After Terayama entered Waseda University, his correspondence with Yamagata continued. Yamagata himself became even more enthusiastic about haiku and published – at his own expense – a collection of haiku titled ‘Dozo’ (bronze statue) to commemorate his graduation from high school. When Terayama was asked to write an afterword to the book, he sent a wonderful tribute titled ‘To Yamagata Kenjiro – the boy who creates fire.’

Terayama invited him to Tokyo and after graduating from high school, Yamagata entered the Faculty of Law at Chuo University. They began an intense relationship that involved Yamagata staying in Terayama's lodgings.

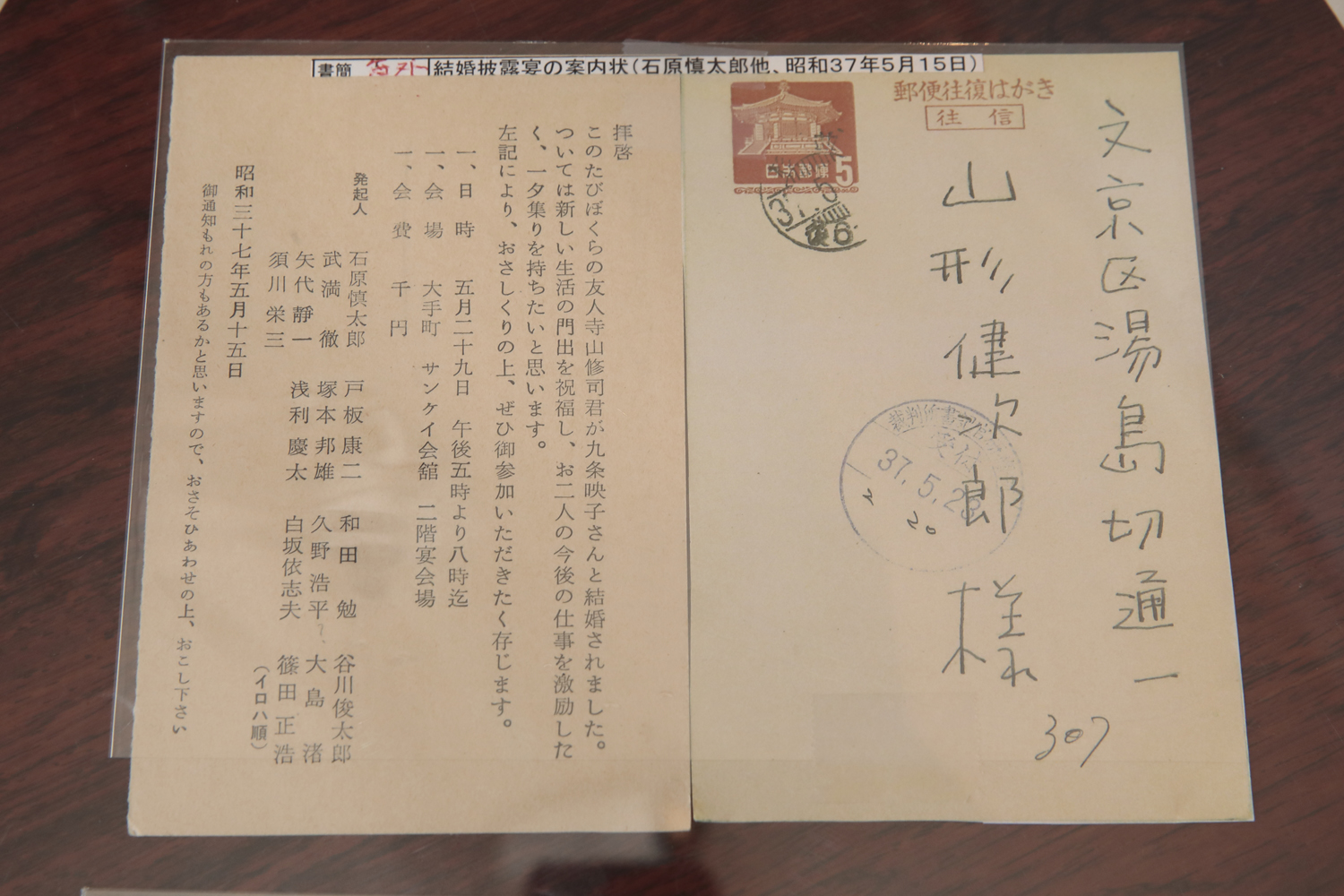

An invitation to a wedding reception. The list of organizers includes many eminent names

After dropping out of college, Terayama wrote radio dramas, plays and movie scenarios, but in 1967 he launched the Tenjo Sajiki Theater Company and rose to fame.

Yamagata, on the other hand, made the U-turn back to Hokkaido in 1963 at the age of 26, where he chose to work as a clerk at the Sapporo District Court.

“As a young literary enthusiast, I tried to become a writer, but gave up after 10 years and became a government official,” says Yamagata.

Yamagata’s study, which provides a glimpse of his ‘young literary enthusiast’ past

Yamagata retired after 10 years of service in public office. After opening a certified administrative-procedures legal specialists office, he began a career as an entrepreneur.

It was May 4, 1983 when Terayama died of sepsis brought on by peritonitis and cirrhosis of the liver. Yamagata had lost his mother in January of the same year, and Terayama’s subsequent death came as a shock to him, leading to a period of stupefaction.

“I realized that I could no longer go on like this, as I had failed to be a dutiful son to my mother, who had worked hard to raise me, and that I had missed the chance to repay Terayama, I decided to start living life a little more seriously.”

Yamagata had sealed his past with Terayama. He had kept it a closely guarded secret and told no one as he carried on his business, eventually becoming the representative of four companies and an auditor for seven more.

Terayama’s writings and research materials can be picked up and browsed over

It was in 2002 that Yamagata publicly announced his exchanges with Terayama, on the occasion of the Shuji Terayama Exhibition at the Hokkaido Museum of Literature. The exhibition was supervised by Yamaguchi Masao, a cultural anthropologist who was a close friend of Terayama. Yamaguchi was president of Sapporo University at the time, and, in addition to the exhibition at the museum of literature, plays, readings, screenings and live performances of Terayama’s work were held in conjunction at Sapporo University, cinemas and theaters.

“I took the liberty of holding a private retrospective Terayama Shuji exhibition at the same time, thinking it would be a good opportunity for people to see the materials,” explains Yamagata.

The exhibition featured a collection of Terayama’s letters in a gallery on the first floor of his company's building. The exhibition surprised Yamaguchi, who came to see it.

“If Mr. Yamaguchi had not been in Sapporo, I might not have shown the contents to anyone. The response to the exhibition was so great that the following year we were asked to lend the letters to the Setagaya Literary Museum for its ‘The Return of Shuji Terayama’ exhibition, and opportunities to talk about Terayama increased.”

The space that had been used as a project gallery was renovated into a museum

It’s quite extraordinary that letters exchanged during high school were kept all this time.

“It just happened that way. When I published my haiku collection, I printed 300 copies for 70 yen each, and presented them to my favorite haiku poets, and some of them sent their reviews. Even though I stopped writing haiku, I kept some of Terayama's letters as mementos of my life.”

In 2019, the gallery on the first floor of the company building was renovated to become the Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo, and a permanent exhibition began. Considerations are being made to incorporate the museum into a foundation to ensure its continuation in the future.

(Photo courtesy of the Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo)

Shuji Terayama Museum, Sapporo

Yamanote 7-jo 6-chome 4-25

Nishi-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

Open weekdays 13:00–17:00

Closed Sat., Sun. and public holidays

Tetl.: 011−614−2918

Admission free

Website