Tradition maintained by new challenges

vol.10Mizuno Hirotoshi, CEO, Mizuno Some Kojo Co., Ltd. / Asahikawa City

Photographs by Ida Yukitaka

Translation by Xene Inc.

Underground water is necessary for dyeing

Mizuno Some Kojo’s main business is the traditional Japanese culture of shirushizome (print dyeing), in which business logos, family crests, names and such are dyed onto fabric and used as trademarks and the like. But why did the founder of the company choose inland Asahikawa rather than Hakodate or Otaru, where the economies were more developed? According to the 4th-generation CEO, Mizuno Horotoshi, “Asahikawa is blessed with underground water from the Taisetsu Mountain Range. In the olden days, the company dyed kimonos and so Asahikawa was probably chosen for the quality of its water. Wherever there is a textile dyeing industry, there is always an abundant supply of water.”

With the early establishment of transportation links from Central, Northern and Eastern Hokkaido, Asahikawa soon became an important distribution interchange. Despite being located in an inland region, the company began receiving orders for flags that were hoisted on fishing boats to indicate bumper catches. This was probably due to its links with markets around Hokkaido that dealt in seafood. The products that the Mizuno dyed-goods shop handled changed from kimonos to aprons, fishing flags and noren curtains that are draped at the entrances of restaurants and the like.

Characters and logos are painted with a dye resistant paste before the fabric is dyed and the paste is washed off, leaving the character or logo standing out in white.

A frame is placed on the fabric, and a dye resistant paste is painted onto the parts that need to be kept white.

The skills of the craftsmen and women are the assets of the company

There are two techniques used in the shirushizome maintained by Mizuno Some Kojo. A feature of hikizome, in which the dye is applied by brush, is that the dye soaks through to the reverse side of the cloth. With nasen, or print, a design template is placed on the cloth and a large spatula, known as a squeegee, is used to apply the dye.

One thing that surprised me during my visit to the factory was the young age of the craftsmen and women who are maintaining the traditional techniques. The average age is 35. “The old craftsmen and women don’t even teach how to make the colors. In that way the traditions cannot be continued. Here, the dye mix is made into a recipe and color samples are made so that even new employees who have just joined the company can mix the colors. Difficult skills, too, are conveyed in easy-to-understand images, and the entire process can be taught in about three years.”

Paste made from seaweed and mixed with dye is used in the nasen technique.

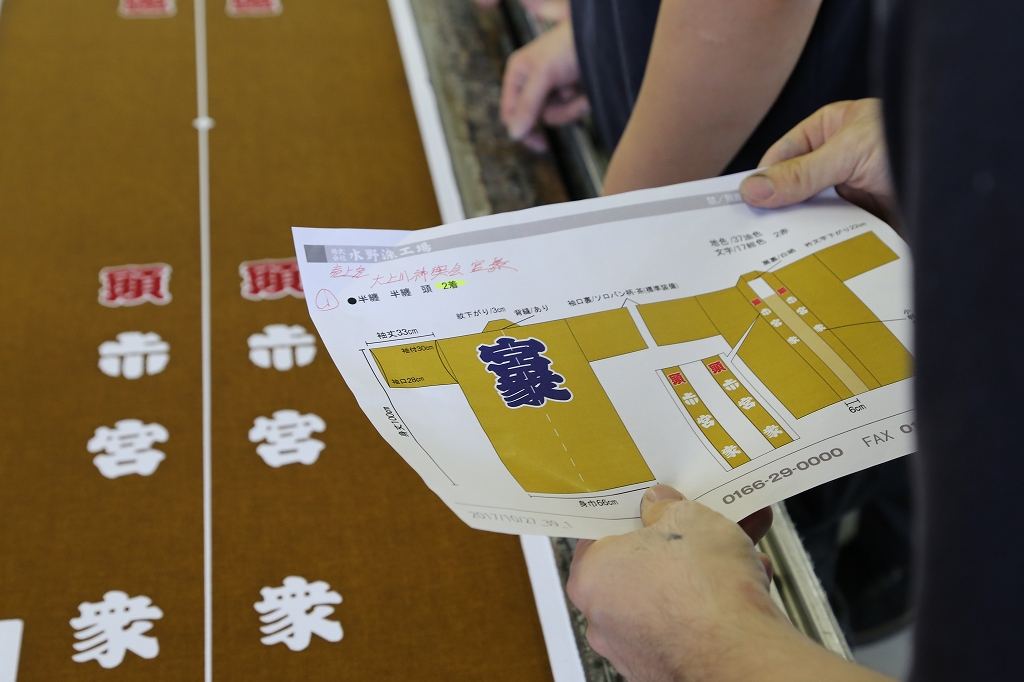

Finishing off the product while confirming the plans

Expanding the overseas market

14 years ago, the company opened a shop in Asakusa, Tokyo, and now it has three shops in Tokyo. “Orders via the Internet now mean that sales outside Hokkaido make up for 80% of the turnover.” This ability to always think ahead has meant the aggressive stance remains strong.

Mizuno Some Kojo is currently making inroads overseas and has begun holding exhibitions at gift shows with a plan to starting up wholesale businesses in Los Angeles and New York.

Mizuno Some Kojo Co., Ltd.

Taisetsu-dori 3-chome 488-26, Asahikawa, Hokkaido, Japan

Tel.: 0166-29-0000

Website